Fishing is more than taking fish out of the ocean. Depending on the fishing method, there are issues with bycatch, waste, and plain inefficiency to deal with. And one fishing method releases more CO2 than the entire airline industry. Yes, really. Let’s dive in.

What to Expect in this Article:

- Majority of Ocean Trash Soup from Fishing Activity

- Fishing Methods: Fishing isn’t Fishing

- High-Sea Fishing: Inefficient Destruction

- Small-Scale Fisheries: The Future of Fishing?

- Solutions: What Can We Do?

Majority of Ocean Trash Soup from Fishing Activity

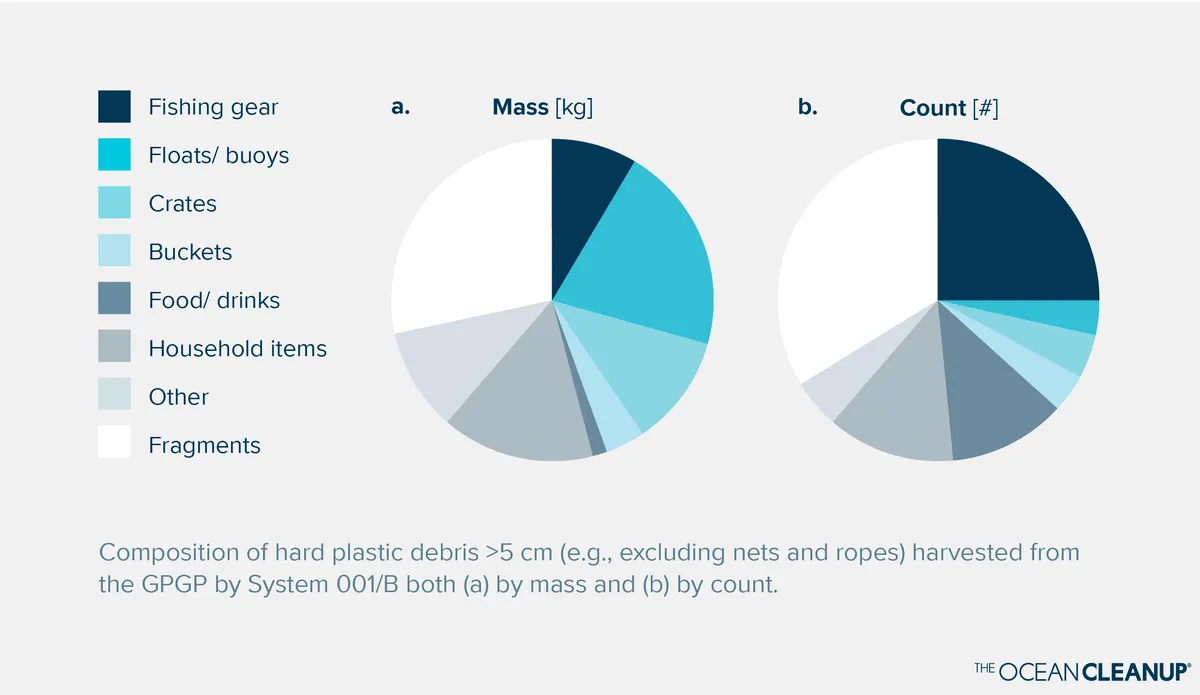

The Ocean Cleanup project just released a new study about what exactly floats around in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, one of the giant trash soup gyres in our ocean. Even I was surprised at the numbers: 75% to 86% of the plastic they found there originated from fishing activities at sea. But sure, let’s ditch the straw and buy an overdose of reusable cotton totes.

Okay, granted, plastic that is lost at sea has a higher chance of ending up in the garbage patches than plastic from land, but it’s still astonishing just how much waste the fishing fleets of industrialized nations add to the ocean. The kind of waste that ends up on beaches looks very different from the kind of waste collecting in the trash gyres.

So, while stemming the never-ending flow of plastic waste we add to the environment is definitely an absolute necessity, the powers that be are again focusing (or distracting us with?) on the wrong thing.

The Ocean Cleanup Project lists in their shortcomings that they didn’t take aquaculture into account—so, some of that waste might be from breeding fish and other seafood instead of catching them. This just reaffirms my belief that aquaculture is not the solution. Don’t worry, aquaculture will be a topic here soon, too. And so will plastic pollution’s impact on marine life, for that matter.

Okay, back to the plastic soup in our oceans: The oyster spacers made up less than a percent of the total, so this is probably offset by trash they didn’t consider fishing-related. Around Saint Helena, a pretty isolated island in the South Atlantic, the Ocean Conservancy reported an “exorbitant number” of plastic bottles, and after some digging came to the conclusion that these are likely from the fishing fleets in the area. So, some of the plastic bottles—and many other items—in the garbage patch are likely fishing-related, even if they aren’t directly fishing gear.

But either way, the amount of fishing-related debris in the ocean is unbelievable. If what the Ocean Cleanup collects is even remotely representative, about 80% of the weight of the trash in the Great Pacific Garbage patch is from fishing activities: nets, ropes, line, plastic crates, and so on.

But what kind of fishing causes this waste? Is all fishing created equal? No, of course not.

Fishing Methods: Fishing isn’t Fishing

Fishing methods can be lumped together into eleven methods in four groups: manual, nets, lines, and traps. But they all differ widely in their impact on marine life and ecosystems.

The biggest issues of these fishing methods are: by-catch, resource use, habitat destruction, and then a whole list of social issues.

By-catch is anything that the fishers didn’t mean to catch. The cliché example is dolphins getting tangled in fishing nets, but there are all kinds of species getting caught or entangled in all kinds of fishing.

Habitat destruction can be physical, so something like sediment getting disturbed or rocks getting damaged, or biological, so something like coral breaking off or plants getting destroyed. Remember, corals are animals, so breaking chunks off a reef is biological damage, at least in part.

Resource use includes both the fuel spent to get to where the species they want to catch is and having to replace equipment and such.

And then there is the whole realm of social issues: exploiting cheap workers, taking fish away from the local fishermen to ship them across the entire globe, bribing the “impartial” observers, commercial interests in certification labels, and so on. As Naomi Klein said in On Fire, social issues cannot be separated from climate action. But, as they aren’t specific to catch methods, they won’t be a topic today.

Bombed: Blasted to Death

One type of fishing that is often entirely ignored in lists of fishing methods is blast or bomb fishing. This is because the practice is illegal in many parts of the world. But, while that’s the case, there are still plenty of people blasting entire ecosystems to smithereens.

Illegality doesn’t mean it isn’t done. According to a review from last year, “coral reefs in much of Southeast Asia, Tanzania, the Red Sea, and other areas in Asia, Africa, Europe and South America” are still getting destroyed at a large scale. And according to the paper, poverty is usually not the cause for this.

Most people have heard of Jacques Cousteau, probably, the founding father of scuba diving, and a celebrated ocean explorer, author, and filmmaker. Unfortunately, while he might’ve been a leader for ocean conservation later, his earlier explorations were rather harmful and disgusting. I could barely watch one of his 90-minute films.

“In order to take back a complete sampling of the reef, we must, unfortunately, cause some damage.”

No, no you don’t, Jacques.

“Commercial fishing with dynamite is illegal, an act of vandalism, but for the purpose of scientific study, it is the only method for taking a census for all the varieties in an area. For every ten fish killed, only one or two float to the surface. The rest sink with injured air bladders.”

While I have a hard time trying to justify these words with “ah, this was 70 years ago,” he brings up one of the worst parts of blast fishing: it’s inefficient as duck. Most of the killed fish just sink to the bottom and aren’t collected by the fishers. And that’s just the fish.

To quote that review paper—which, by the way, looked at 212 other papers—says that “blasting is widespread, misreported, and ongoing.” And they blame lack of proper enforcement. So yeah, blasting is illegal in much of the world, but it’s not over, so I decided to include it here.

On a more selfish note: they think Marine Protected Areas are a solution. Yay! My bachelor thesis topic.

Trapped: Fishing with Traps

One of the items floating around as trash in our oceans—and rivers for that matter—is traps. There are various traps for all kinds of aquatic animals. From eel traps to lobster cages, smart people have figured out how to set traps for anything that can be tricked into captivity.

The teacher’s aid for my previous class was doing research on improving the selectivity of eel traps, so there is definitely progress being made, but no-one seems to be rethinking the entire idea.

Traps and pots have been ranked in the middle when it comes to collateral damage, a term used to sum up the habitat and bycatch impact. In other words: could be better, could be worse.

Hooked: Fishing with Lines

Fishing with lines includes some of the worst—though not the worst—methods of fishing. Longline fishing is a popular commercial method of fishing. There are pelagic longlines, so longlines away from the bottom of the ocean, and demersal longlines, so longlines near the bottom. Demersal is just a fancy word for on or very near the bottom of the ocean. We’ll get into the zones of the ocean in the future, of course.

With longlines, there’s a mainline which has the branchlines or ganglions attached. And each of those branchlines has a hook and sometimes a lightstick to attract certain prey.

And when I say longline, I mean long ducking line. According to NOAA, US longline sets are on average 45 kilometers (28 miles) long. That’s a long-ass line.

While longlines are less harmful to the habitat than most fishing methods, they have a great risk of bycatch and entanglement. And then there’s the sheer amount of plastic that stays in the ocean because sometimes the lines can’t be recovered.

But, as I said, there is a style of line fishing that is one of the least impactful of the bunch: pole-and-line fishing. And that’s exactly what you think it is—well, kinda. It’s a pole with a line. So, traditional fishing, right?

As I said, kinda. When one fisherman does this or a few anglers stand on a pier, this is actually no big deal. Except for highly vulnerable areas like the Baltic Sea—the ocean thirty minutes away from me—this is not the problem. Yes, there are issues. Yes, some idiot fishers cut their lines and throw them in, not realizing that they are adding an entanglement hazard for marine life and divers. Yes, some line will be lost. And yes, there’s the issue of barotrauma and, well, holes in the fish’s mouth, but all of these are minor compared to other methods.

However, don’t think that that can of tuna advertising with pole-and-line caught fish is necessarily sustainable. Many of the commercial fleets are ducking efficient. Some use water to stir the surface to attract the school of fish, and then they take out one after the other after the other. Seriously, it’s hard to believe how fast they are at taking out the fish—and to fill up the boat.

My main issue remains the lines themselves. While there are biodegradable fishing lines now, they are still less reliable than nylon line. Things are happening, but it’s not the norm yet. That needs to change. Still, fishing with pole and line at a small scale is definitely one of the better options.

In the Net: Gillnets

Gillnets are essentially walls of net that trap fish—by their gills. Gillnets have a specific mesh size, so the holes are a certain size, that lets the fish stick their heads through, but not the rest of their body. They then get trapped with their gills, and the more they struggle, the more they get tangled. Sounds like a wonderful experience…

Gillnets exist in bottom and midwater versions, so they can either be set on the bottom of the ocean to catch demersal fish like flounders, or they can drift to catch species midwater.

In the case of drifting gillnets the bottom of the net is weighted with lead, while the top is kept afloat by buoys or other floaty things.

While gillnets are considered more selective with reduced bycatch, they still pose a real risk to marine mammals, sea turtles, and other marine life. Remember that sea turtles and mammals need to breathe air, so if they get entangled, they don’t have a lot of time for a rescue before they drown. According to NOAA, the most-caught mammals are large whales like humpback, fin whales, or right whales, dolphins, sea lions, and seals. And that’s just the turtles and mammals. Sharks, crabs, and many other marine animals get tangled too.

These gillnets are constantly improved to make them more selective with things like acoustic devices to warn dolphins and whales, and dedicated break points to allow large whales to break through, and such, but they are far from perfect.

And, also, they are made from nylon in most cases, so more plastic in the ocean if they get lost, damaged, abandoned, or thrown overboard after the end of their usefulness.

In the Bag: Purse Seines and Midwater Trawls

Purse seines might have a weird name, but they are one of the most common fishing methods used today. They are essentially walls of nets, but instead of just drifting or sitting around, they are pulled closed around a school of fish.

Much like with the gill nets, there are floats at the top and a weight at the bottom to make sure the wall stays a wall until it is pulled tight, pursed, into a bag.

And this is another massive method. The seines can be multiple kilometers long and more than 200 meters deep. Massive!

Unfortunately, purse seines are not selective. They just scoop up whatever they can bag. And in addition to getting tangled, there is now also the enormous weight of the many, many fish and unintentional victims that squeeze turtles and mammals to death. And there doesn’t seem to be much done to minimize this.

Midwater Trawls are another in-the-bag kinda method, but a tiny bit more selective. They are somewhere between bottom trawls, which we’ll talk about in a moment, and purse seines. A giant bag of net is dragged through the water at the height the target species is expected, and then pulled onboard.

Scraping the Ocean Floor: Dredges and Bottom Trawls

And that leads us to the most destructive methods of fishing: dredging and bottom trawling.

In either case, something is dragged across the seafloor to herd and capture the wanted prey.

Bottom trawling drags a net across the ocean floor. Floats, line tension, and weights keep the net open. Depending on the surface, there are attachments to be more efficient or to reduce bycatch. Typical target species are anything near or on the bottom like whiting, crabs, shrimp, flounders, and even dogfish—which is a shark, by the way.

Even worse are dredges, which not only scrape the bottom of the ocean but can also be penetrating by using pressurized water jets to chase animals out of the sediment. They are used for things like oysters, scallops, clams, and such.

Both of these methods have the same common bycatch as nets with risks to sea turtles and marine mammals, but also to many other kinds of animals.

There have been improvements to these two methods like turtle deflector devices and a lot of research into mesh sizes, shapes, and how they affect different fish. While one species might flee up, another might flee down, so making the top mesh different from the bottom mesh can allow one species to flee while the other is stuck.

A big, often overlooked, issue with bottom trawling (and any other fishing method that disturbs the ocean floor) is carbon dioxide emissions.

When I first heard that bottom trawling releases as much carbon dioxide as the airline industry, I was very surprised. I hadn’t even thought about it. Yes, yes, I knew about the ocean buffering our emissions and how carbon gets to the deep ocean. I knew all that. But I had never thought about bottom trawling affecting this.

According to a very interesting study from 2019, “marine sediments are the largest pool of organic carbon on the planet and a crucial reservoir for long-term storage.” If we leave it alone, it stays there for a very long time. But if we duck with the sediment, we stir stuff up and add the carbon dioxide back into the water. The water is fully saturated, though, and can’t simply hold more, so the carbon dioxide bubbles up.

Between 2016 and 2019, about 1.3% of the ocean floor were dredged or trawled, releasing an estimated 1.47 Pg of aqueous carbon dioxide. 1.47 petagrams are 1,470,000,000 tonnes. So, that’s a crabload.

And I haven’t even talked about the actual destruction of the seabed caused by dragging, scraping, or even penetrating dredges or trawls. Between bycatch, plastic pollution, habitat destruction, and releasing a crabton of carbon dioxide, it’s hard to even remember all the reasons I detest trawls and dredges so much.

High-Sea Fishing: Inefficient Destruction

While high-sea fishing is technically not a method but a location, it’s still worth having a quick look at high-sea fishing.

According to a study from four years ago, more than half of high-sea fishing wouldn’t be profitable without subsidies.

Yes, without your hard-earned tax dollars, high-sea fishing wouldn’t be able to keep going the way they are. And that’s only going to get truer with the rising cost of fuel, declining fish populations, and general crises.

Small-Scale Fisheries: The Future of Fishing?

When people think about fishing, they typically have idyllic pictures of small fishing boats in mind that leave a small harbor at sunrise. And, watching the fleet return to Morro Bay while enjoying some breaded and fried seafood is definitely enjoyable, but this is not how fishing looks in much of the world.

While there are still smaller local fishing operations all over the world, they are having a harder and harder time thanks to giant industrialized fishing nations. Remember that study from the Ocean Cleanup project? 34% of the fishing-related items could be traced back to Japan, 32% to China, 10% to the Korean peninsula and 7% to the US.

Just to have it mentioned: this is the origin of the plastic and not necessarily that of the fishers using the gear. It might be that an Indonesian fishing vessel used crates made in China, for example, but this doesn’t really change the general issue: industrialized fishing vessels.

China’s fishing fleet is 17,000 vessels strong, and there’s evidence of illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing. And, in addition to their own fleet, they finance port constructions and fish factory projects all over the world. For example, they helped build a port in Mozambique in 2019, which they then secured a 5-year agreement for to use the port for their own fishing. In 2019, they were the main fishers in the Sofala bank, leaving local fishermen to look for alternative solutions. And they wonder when people turn pirate…

Defining small-scale fisheries (SSF) isn’t as simple as it sounds. In many cases, it’s done by limiting the size or weight of the fishing boat or by how technologically advanced the equipment is. But that would mean a single person very efficiently catching 50 fish is large-scale while someone who very inefficiently catches 50 tonnes is small-scale. Even after reading an entire paper reviewing different definitions, I’m not sure what the perfect definition is.

My issue is that I’d define small-scale fisheries by their intent and mindset, and that’s not something you can use to write policy.

In Indonesia, for example, a small-scale fisher is anyone who fishes with a vessel grossing less than 10 tons. As small-scale fishers are excluded from many fishery management measures, this means a crabload of catch isn’t even properly recorded.

So, finding a proper definition, is clearly necessary, but it might be easier to not exclude small-scale fishers from policy while limiting what large-scale operations are allowed to do.

Why is it okay for a Chinese vessel to burn endless amounts of emission-heavy fuel to get from their overfished China Seas to the global south and take fish away from fishermen there?

Again, I’m not singling out China. Japan slaughters dolphins to have less competition for the fish—entirely ignoring that they did this to themselves by overfishing the stocks. Two percent of Norwegians still eat whale meat—and there is still a whaling industry in Norway. In 2022, the quota for mink whales, for example, was almost a thousand. And the Baltic near where I live is in dire straits between severe overfishing of especially cod and herring to a point where cod is likely unsalvageable and an expanding layer where oxygen is too low to support most fish.

But, as always, there is a solution, and it’s rather simple: marine protected areas, proper fisheries management, and some international cooperation. For now, enforced labels on seafood would already be a start. If consumers knew how and where their seafood was caught, they would at least be able to make an educated choice.

Marine protected areas are the topic of my bachelor thesis, so I’ll definitely talk about that topic here. For now, let me just say that completely protecting at least a third of the ocean—though we could go as high as 70% without reducing food production—would solve a crabton of issues.

And remember, stopping overfishing, especially with the most harmful methods, would help with greenhouse gasses, too. And smart researchers already confirmed that sequestration would increase again if stocks are allowed to recover.

So, as so often, the main issue standing in the way of progress, solutions, and a healthy planet are those who would exploit anything and anyone for their own personal gain.

It’s time to demand change.

What’s Next?

If you feel like going down a humans-suck rabbit hole, keep reading to learn more about why fisheries management doesn’t work. And if you need a palate cleanser, I suggest learning about lobsters instead.