Shrimp are the cleaners of the ocean and can even influence the current of the ocean. I’m a marine ecologist, and today I’ll tell you all about shrimp. They are way more interesting than you think!

Most articles and videos about shrimp are about one of two things: mantis shrimp or the Neocaridina so popular in the aquarium hobby. So, you’ve got a choice between shrimp that aren’t shrimp or shrimp in unnatural environments. So, let me make a case for the rest of the shrimp world, which is a lot less boring than you think.

Stunning pistol shrimp shoot bubble bullets at their prey—and can even hide submarines, while other snapping shrimp are the bees of the ocean with an exceptional social life.

Harlequin shrimp are sneaky bastards who exclusively feed on sea stars, even the crown-of-thorns that is so devastating to coral reefs.

Various cleaner shrimp daringly crawls into the mouths and gills of fish that need a cleaning more urgently than a quick bite or sweep the yuck off rocks.

Oh, and then there’s the sexy shrimp—no, I’m not kidding—a tiny shrimp that looks like it’s constantly wiggling its butt.

And despite their usually small size, researchers found that they can influence the current of the ocean enough that we need to add them to ocean models. That’s a tall feat for something this small.

I told you there is a lot more than those two popular shrimp friends in the shrimp world. Let’s dive in.

What to Expect in this Article

- What Kind of Animals are Shrimp

- Lifecycle of Shrimp

- The Mantis Shrimp: Quite the Punch

- The Snapping Shrimp: Bubble Bullets

- The Harlequin Shrimp: Defender of the Reef

- The Glass Sponge Shrimp: Till Death Do Us Part

- The Cleaners of the Sea

- An Unfortunate Truth about Shrimping

What Kind of Animals are Shrimp?

We left things at the crustaceans last time, the group that contains everything from shrimp, lobster, and crayfish to barnacles. To get from there to the mantis shrimp—have I mentioned it’s not a shrimp?—and the true shrimps, there are numerous steps.

Within the crustaceans, we find the Multicrustacea, the clade that includes the barnacles, copepods, and the Malacostraca which in turn includes the Phyllocarida, a group with weird crabby things that survived since the Crustacean, and the Eumalacostraca.

Within the Eumalacostraca, we’ve got the Hoplocarida—our mantis shrimp—the Syncarida, a clade of freshwater crustaceans that look a lot more like legged worms than anything else, the Peracarida, so amphipods and isopods, and the Eucarida.

The Eucarida are a giant group witht he Euphanasiacea, which includes the krill, the Amphionidacea, planktonic shrimpy things, and the Decapoda. Decapoda, decapoda. You’ve heard that before, right? Yes, you have! It’s the group the coconut crab we talked about belonged to.

ithin the Decaopoda, we’ve got the Dendobranchiata, the prawns, and the Pleocyemata. There are plenty of groups in teh Pleocyemata that I won’t even list here (check the image above), but also the Brachyura, the short-legged crabs, the Anomura, the hermit crabs, the Astacidea, the lobsters and crayfish, and—finally!—the Caridea, the true shrimp.

See, mantis shrimp aren’t shrimp. There were a crabton of words between them and the true shrimp.

Lifecycle of Shrimp

The life of shrimp starts as eggs, which sink to the bottom, where they develop until the larvae are ready to hatch. Once hatched, the nauplius larvae join the plankton community, as they are still pretty shitty swimmers. They undergo multiple stages of shedding growing and shedding, each time getting better at swimming and more developed.

As a protozoaea, the mouth parts and abdomen develop, and more growing and shedding ensues, until the little friends turn into mysis shrimp—yeah, those aren’t actually a kind of shrimp. Though, there are imposters in the aquarium trade that aren’t even shrimp. Ah, well. Shrimpy mysis shrimp have early legs and antenna—almost real shrimp!

Finally, they turn into their postlarval stage, essentially miniature shrimp. Some shrimp like the common shrimp or brown shrimp now feel the urge to migrate to the brackish waters of estuaries for food. Very efficiently, they ride the tides there, riding the floods while spending ebb tides on the bottom. Smart!

The juvenile and subadult stages are pretty hard to distinguish from the adults, but it’s essentially when their reproductive organs develop into full functionality. It’s also when the migratory shrimp return to the sea searching for a suitable mate. While some shrimp can migrate hundreds of miles along the shore, they like to stay close to the shore—probably trained to give their offspring an easy path to the estuaries.

The Mantis Shrimp: Quite the Punch

Despite not being shrimp, I get why people love them so much. They are pretty clam cool!

Mantis shrimp have the fastest punch of any animal thanks to a pair of hinged arms. And they pack quite the punch, not only by speed, but also by strength. They can fend off an octopus, smash through a quarter inch of glass, or draw blood from a human even through thick neoprene boots. Impressive!

They have one of the most complex eyes of any animal, with twelve color receptors and the ability to see UV light and two kinds of polarized light.

But, as there a literally thousands of videos about these non-shrimp shrimp, let’s move on.

The Snapping Shrimp: Bubble Bullets

While the mantis gets all the attention, there is an actual true shrimp who deserves some praise. The snap of some species of pistol shrimp can get louder than an actual gunshot—210 decibels.

But while shooting bubble bullets is ducking spectacular, I especially like the symbiosis between pistol shrimp and gobies. We’ve seen gobies share dens with shrimp in Catalina, and it’s pretty darn cool.

Shrimps are natural burrowers, so they maintain the den while the goby stands watch. Look closely, and you’ll see the shrimps antenna keeping permanent contact with the goby. The goby has much better eyesight than the snapping shrimp, so they are the perfect watchmen. In return, they get shelter in the perfectly maintained burrow of the shrimp. The really fun thing is that the pairing doesn’t seem to be coincidence: more active gobies and shrimp look for more active partners. The personality of the roommate matters—even in the animal world.

And there is more to be loved about snapping shrimp that deserves them the nickname “bee of the ocean.”

In marine environments, social structures are rarely very social. What’s even rare is something called eusociality, so a social structure where females raise the offspring cooperatively and divide the reproductive labor. Examples of this are bees, ants, and, of course, a genus of snapping shrimp.

The sponge-dwelling snapping shrimp of the genus Synalpheus are the only ones to exhibit this special social structure. They breed communally and raise their young together. There is no single queen be, uh, queen shrimp, though, but instead multiple breeding pairs.

Animal social structures will definitely be a topic on here soon. Way too interesting to ignore.

The Harlequin Shrimp: Defender of the Reef

Harlequin shrimp are very picky eaters—and very sneaky bastards. They feed exclusively on sea stars, multiple of them working together to flip them over and detach the legs. They probably get away with it because they are so ducking pretty—I’m kidding, of course. They are stunningly pretty, though.

Their very selective diet is good news for coral reefs, though. They are eating enough of the devastating crown-of-thorns starfish (Acanthaster planci) to make a dent. Of course, scientists are now considering adding harlequin shrimp to reefs to protect them, but I can already see the headlines: “Invasive harlequin reef devastate local starfish populations.” Yeah, probably a good idea, right?

The Glass Sponge Shrimp: Till Death Do Us Part

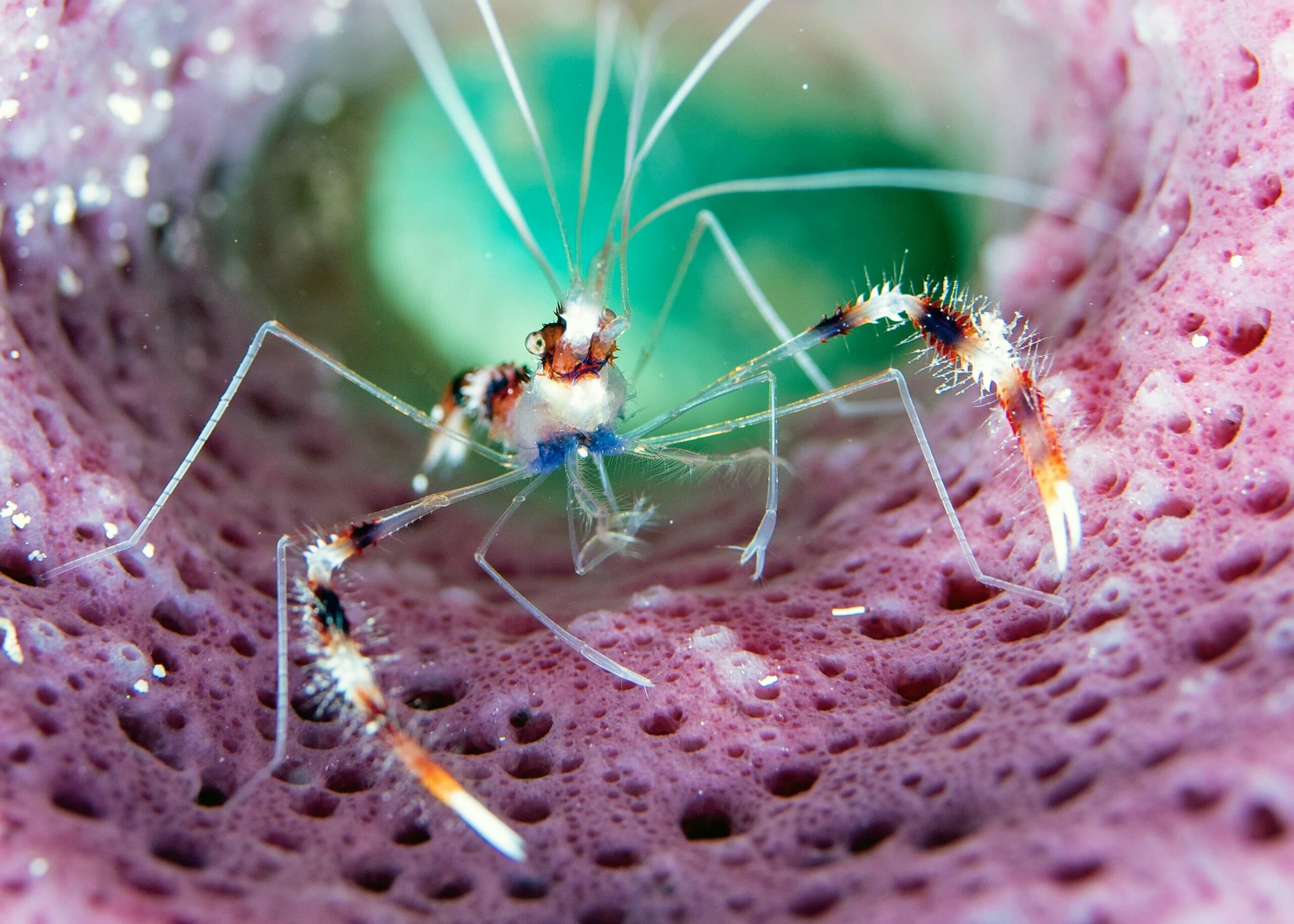

Venus flowerbaskets are very pretty glass sponges. Their sponge spicules, tiny needles of essentially glass, create intricate structures that look like lace. Despite looking like they’ll fall apart at the slightest touch, they are pretty stable structures. Food particles get stuck in these spicules—a feast for the tiny glass sponge shrimp.

Glass sponge shrimp pick a mate when they are still juveniles, small enough to just walk into the web of glass. And then they spend the rest of their lives there, soon too large to even attempt a divorce. Literally, till death do us part. In a perfect example of coevolution, the shrimp have evolved to need the shrimp, loosing parts of their gills and some strength in their shells, perfectly adapted to the captive lifestyle. The sponge, in turn, has adapted into a glow-in-the dark beacon for the shrimp, or at least, that’s what we currently think.

Oh, and the sponge is actually getting something out of the relationship. As established, shrimp are the cleaners of the sea, so the sponge’s spicules are always perfectly clean and ready for more particles to get stuck that the sponge can feed on—and, of course, share with their shrimp. Gotta love evolution!

The Cleaners of the Sea

Being ducking good at keeping their environment clean is what shrimp are all about. While some species sweep the yuck off rocks or out of the sediment, others are much more daring. At so-called cleaning stations, daring little cleaner shrimp crawl all over their customers. They crawl over the scales and skins of fish that need a scrubbing more urgently than a quick shrimp-sized snack. They even enter the gills or the mouth of their customers to get dirt and parasites out of all nooks and crannies.

And usually, this works very peacefully. The shrimp are even thought to signal their services, sometimes using anemones for extra advertising, while the fish change their colors to wave the proverbial white flag. And, as everyone benefits, there are only occasional idiots who break the deal. Sometimes, the shrimp take a bite off the fish’s mucus or the fish take a nibble of their cleaners. But this is rare, and usually immediately punished by the reef community. Fascinating.

Unfortunately, like so many species, especially tropical cleaner shrimp, so vastly important for the health of the coral reefs, are vulnerable to the rising sea temperatures.

An Unfortunate Truth about Shrimping

I know, I know. Climbing the Tree of Life, so keep the doom and gloom to a minimum. Okay, give me thirty more seconds.

Humans eat a crabload—or should I say shrimpload?—of shrimp. 3 million tons of shrimp are consumed every year in the US alone. This overconsumption has left even resilient abundant species like the common or brown shrimp, the Crangon crangon declining‚ and that even though shrimp hugely benefited from human overconsumption of the fish that eat them.

Shrimp were originally caught in hand-held nets that looked like a fishing net attached to a slingshot. Later, horse-drawn trawls were used to catch more shrimp per unit effort.

Even modern shrimping done with upgraded versions of trawling gear still have a negative impact on the climate and the local ecosystems by disturbing the sediment and the related infauna and epifauna, so organisms that live in the sediment and on the sediment. Have I mentioned that bottom trawling releases more carbon dioxide than the airline industry?

Recent years have mostly been wasted on improving trawling gear to reduce bycatch—oh yeah, bycatch is a major issue in trawling—instead of completely replacing the practice with more sustainable methods.

What’s Next?

Okay, doom and gloom over. And so is this article. Want to learn more? Read this article on why it’s important to protect nature or learn more about crustaceans in this article.