The ocean is huge. The open ocean is a pretty vast space with a whole lot of what feels like nothing. But there’s a lot more life there than you think–and, don’t worry, I’m not talking about plankton.

70% of Earth’s surface is open ocean. Pelagic ecosystems really are the most common ecosystems out there!

With an average depth of 3,700 meters, you probably can’t even imagine just how much fucking water there is in the ocean. We’ve talked about the bottom of the ocean before, and there are marvelously creepy fuckers down there, for sure, but what about the endless nothingness between the ocean bottom and the surface? Well, that “nothing” is the pelagic or open ocean.

While there are plenty of species that migrate between the bottom layers of the ocean and the higher-up waters, I’ve decided to split the pelagic into two: the deep-sea pelagic with all it’s properly creepy creeps, and the upper pelagic with, for the most part, a lot less creepy inhabitants. Though, there’s this thing called a Man-o-war, and that’s definitely properly creepy. Fucking cool too, though.

Anyway, let’s dive in. Actually, let’s dive in quite deep. We’ll talk about the surface and near-surface pelagic next time.

Chapter 1: What life is down there?

As I said, there’s a shitton of life down there. Sure, the open ocean is a vast space and you might not always encounter life large enough to see, but there is still a shitton out there. From tiny planktonic organisms that just float through the vast open ocean to the Collossal and Giant squids, two aptly-named animals, from the unbelievable hairy anglerfish and the Great White shark, from the tentacled to the squishy. There is a lot!

As the deep sea is still pretty cold, dark, and has a shitton of water pressing down on it, animals need to be adapted to the environment. And, fuck, they are.

Bioluminescence is probably the coolest adaptation to the dark down there. I was lucky enough to experience bioluminescent planktonic organisms during a few night dives in California but that’s nothing against the glow-in-the-dark light show of the deep sea. Well, if you are in the right place at the right time to see it.

Organisms can glow to attract prey, to confuse predators, to communicate, or (especially nearer the surface) to blend in.

To keep this doable, let’s skip the hugely important (also bioluminescent) deep pelagic shrimp that float around as a buffet for larger pelagic species. We’ll definitely skip the planktonic organisms there. I know, glow-in-the-dark plankton is fucking cool, but there is much to talk about.

Instead, let’s talk about some really cool fishes!

Chapter 2: Fish of the deep pelagic

There are quite a few really cool examples in the deep sea from hatchet fish with their bioluminescent belly spots for camouflage, lanternfish which flash in the dark to communicate or confuse, and viperfish which are clearly the masters of opening up wide with their weird adapted jaws and monstrous teeth that let them eat bigger food.

But for years, my favorite has been Harry (the nickname my friend group used, because we are a bit immature… okay, a lot.). The hairy anglerfish brings its own glow-in-the-dark fishing lure that attracts prey. The anglerfish opens wide, and in they go. But that’s actually not the coolest thing about them: their sex preferences might just be the weirdest thing you’ve heard in a long time. The male is a lot smaller than the female. At the first opportunity, he’ll attach to a female, and then stay there. They kinda morph together, and the male gets all the nutrients from the female. He still breathes through his own gills, but no feeding or swimming, or anything. He just hangs out and gets fed by the female. But he’s small, so it’s not a lot of work for her. When she’s ready to lay her eggs, she sends some signals his way and he sends sperm her way. So, in essence, she turns on her mate. Cool, right?

And there is so much more! We are barely scratching the surface here. I haven’t even mentioned sharks really, yet.

Chapter 3: Tentacles in the deep sea

You might know by now that octopuses are one of my favorite animals. And, to my delight, there are deep sea pelagic species, too. We already knew there were deep-sea ones like that one we talked about where the female slowly dies for years while tending her eggs? Yeah, that’s a cool on on the bottom of the ocean.

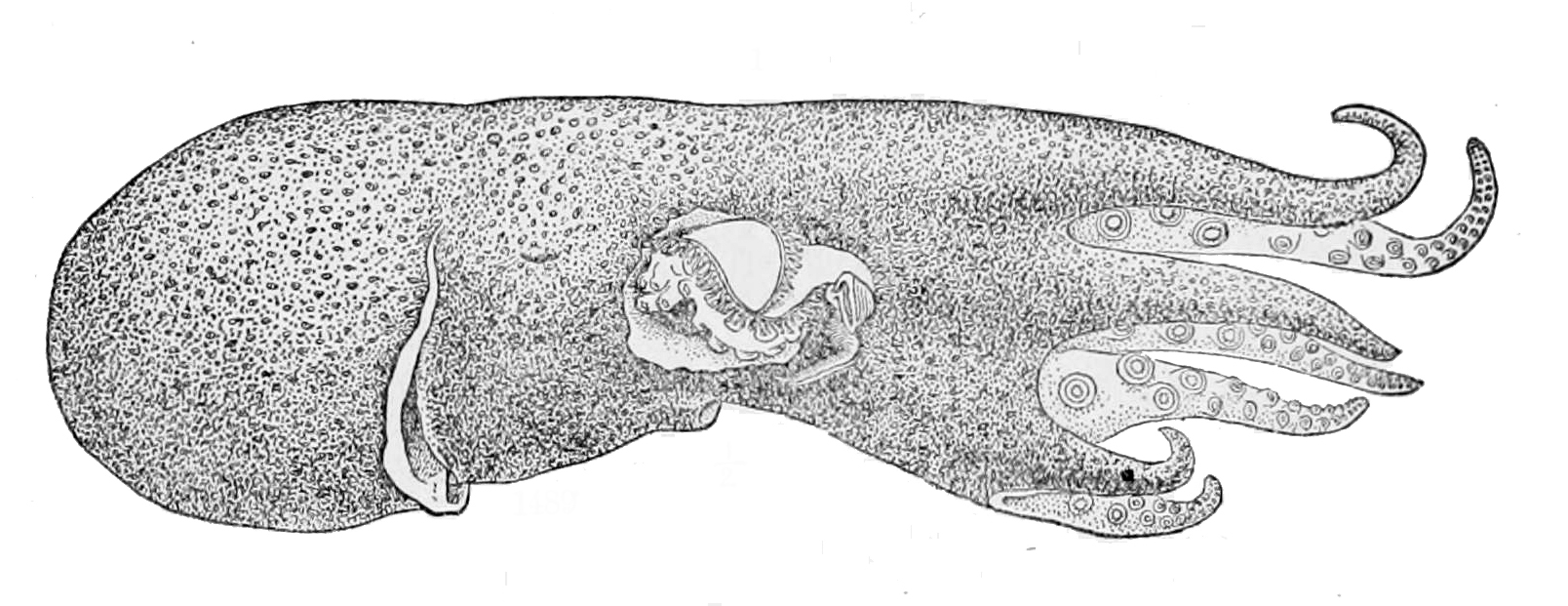

If we stay away from the ocean floor, there is the giant deep-sea octopus which can reach up to 4 meters and weigh up to 75 kilograms. Keep in mind, we know very little about them, so there might even be larger or deeper ones. These, too, have pretty strong sexual dimorphism, so differences between the sexes, and the male is a lot smaller. What’s really cool is that the male’s spermatophore is kinda attached to his face, so he looks like he only has seven arms.

Time for something really cute: the dumbo octopus! Aren’t they adorable? Just imagine swimming around in the deep and dark ocean and encountering one of these cuties? Those ears are fins, by the way. Cute, though. Why do documentaries about the deep sea always focus on the alien creatures that give people nightmares?

Oh, right, nightmares. That’s a great segue to the vampire squids. We talked about them a while back on the Climbing the Tree of Life series, so you might already know that they are neither squid nor octopus but their own thing near the octopuses taxonomy-wise. Again, they might be called vampire squids but they eat detritus, so dead-thing flakes, and won’t suck your blood even if you somehow manage to get that deep to encounter them. What’s really cool, though, is that they can survive in oxygen-minimum zones, so areas where oxygen is so low that a lot of life just can’t support itself. No big deal for the vampires.

Chapter 4: Squishy things of the deep pelagic

Our final group is the squishy things. Yeah, I know, scientist, right? There are quite a few species of jelly things down there from actual sea jellies (aka jelly fish) to sea combs (aka comb jellies), siphonophores (a colonial creature where multiple animals make up one organism, kinda like with the corals but floating and jelly-like), and hydromedusae, so more jelly-like things. It can be really hard to tell them all apart if you don’t know the species.

In general, the deep sea breeds giants and freaks–at least from our very limited human perspective. I’m sure we also look like freaks to them.

But no matter how ugly you might find most of these creatures, we need them all. The pelagic deep-sea is an intricate ecosystem with overlapping webs that affect everything from their direct surroundings to the climate. Let’s not fuck this up.